I wish I had never heard of Hind Rajab

or

Feminist theorising for a world beyond images of dead children

Earlier this year, in February, it was a privilege and pleasure to host my colleague, Prof Marshall Beier, from McMaster University in Canada. While he was in Brisbane, we brought together colleagues for a workshop to think together about the work “imagined childhood” does in global governance.

Marshall has written about how imagined childhood functions as a “social technology of governance”, explaining in a recent piece in Civil Wars:

Like other social categories of identity and difference such as gender or race, childhood is a powerful meaning-making device, a site of political contestation, and always relevant to the (un)making of recognized subjects and objects (2024: 13).

As we sat together in February, I used the provocation of the workshop to extend my previous thinking on the politics of dead children in crisis. I wanted to interrogate what we mean when we use this word, ‘imagined’. This piece brings together my still-in-progress thinking notes from that workshop, with some additional more recent reflections from this week as we reach 200 days (and 75 years) of genocidal violence in Gaza.

I wish I had never heard of Hind Rajab.

I wish I didn’t know she was six years old. I wish I hadn’t seen her handwriting from when she practiced her letters. I wish I didn’t know the name of her mother. I wish I didn’t know the names of the two ambulance workers who went to rescue her. I wish I could get the echo of her words out of my head this week. ‘I’m so scared. Come take me. Please, will you come?’. I wish I didn’t have to imagine her tiny body, sitting in a bullet-ridden car for days on end.

I wish I had never heard of Hind Rajab.

I wish she had lived an anonymous life. I wish she had been able to play on the beach in Gaza, eat ice cream with her siblings, be tucked into bed by her parents. Just a lovely day by the seaside. Just an unremarkable day in an unremarkable life. A happy and safe life, thousands of kilometres from me. I wish there had never been a reason to know her name.

Why is it that we need another dead kid to be a poster child of the preventable cruelty of violence and war?

A child is killed or wounded every 10 minutes in Gaza, according to the UN human rights chief, Volker Turk. Since October 7 more than 14,000 children have been killed. Fourteen thousand Hinds. More than one in every hundred children in Gaza. That is before we count those who have lost parents (more than 19,000), and those still uncounted under rubble.

UNICEF says the Gaza Strip is the most dangerous place in the world to be a child. Never have children been killed so quickly or on such scale. Often wars are mediated through the bodies of children, but what has unfolded in the last three months has been a true war on children. Children’s suffering is central to Israel’s genocidal violence.

I am angry and heartsick. I am furious that once again it is the bodies of children that animate our collective outrage at the genocidal violence in Gaza. I have been thinking and writing about the political work dead children do in international politics for more than a decade now, and I am tired.

The term imagination comes from the Latin verb imaginari, meaning “to picture oneself.”

This root definition of the term indicates the self-reflexive property of imagination. So then, where are we in our imaginings of childhoods? How do we imagine childhood when we encounter images of suffering and dead children in conflict and crisis?

There is so much power and possibility in imagination. Why is it this imagined childhood which animates us? What if we could imagine differently? And alongside this, I am thinking about hope, and what hope does for our capacity to imagine.

If we are (re)orienting ourselves to new ways of imagining, and of the political power of children beyond their death and suffering, I hope the questions might be productive to think about together. Here’s some sketchy thoughts around imagination and hope.

Hope is an emotion of the margins. It is evoked and drawn upon by those looking for ways of being otherwise. The centres of power and privilege do not need to hope, for their success is in maintaining the status quo. It is conservative. Hope is radical.

Rebecca Solnit tells us that hope is an embrace of the unknown. Coleman and Ferreday (2010) describe feminist engagements with hope as “attempts to carefully consider what it might mean to theorise the affirmative”. I’ve been sitting with this call in recent months. Reminded also, that to theorise the affirmative and/or to theorise affirmatively does not mean the loss of the critical edge of feminist critique.

We must be able to imagine otherwise. I am increasingly convinced that we cannot simply account for and dissect the political machinations that rely on compliant reproductions of certain framings of childhood. We must work to theorise but also to enact the possibilities of imagining childhood otherwise.

I’m influenced by the work of brilliant colleagues working on notions of feminist peace — Agnieszka Fal-Dutra Santos, Élise Féron, Jenny Hedstrom, Nicole Wegner, Shweta Singh, Swati Parashar and more. These scholars tell us that it is not simply about ending war, but about dismantling the structures that normalise the violence and rebuilding these in new ways.

This is where, I believe, we can imagine a different childhood to the imagined childhood that animates these violent, patriarchal, paternalistic, racist, and colonial-capitalist frames that not only allow, but revel in conflict and death.

In a wonderful 2018 edited book called the Politics of Outrage and Hope, the editors, Kelly et al, frame contributions through Lauren Berlant’s idea of ‘cruel optimism’. Berlant (2011: 1) says:

A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project … They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that bought you to it initially.

Drawing on this idea, Kelly et al argue it is impossible to ‘imagine a hopeful future from within the bounds of neoliberal capitalist structures’ (2018). I’m moved by this argument, to ask questions, even when I don’t have the answers.

What does a hope which refuses to be compliant look like? How is hope emancipatory or liberatory, rather than reproducing the systems of oppression? How can we be hopeful in our way of reimaging the role of children in mediating conflict and governing war? How can we refuse the imagined childhood that is deployed to maintain or assert sovereign power?

I am increasingly strident about the fact that thinking only about dead children limits our analytical lens—dead children only have imaginative gravitas because of equally potent imaginings of adulthood, both of which are raced and gendered in profoundly powered ways. How do we imagine? How do we ‘picture ourselves,’ and the other?

I’ve returned to these workshop notes on Wednesday 24 April. Day 200 of the genocide.

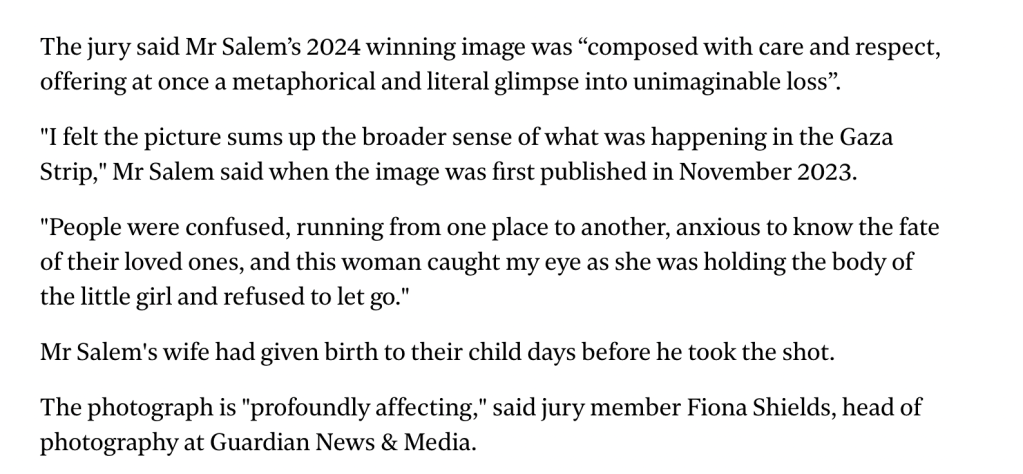

Last week Mohammed Salem, a Reuters photographer, won this year’s World Press Photograph, with an image taken ten days into the genocide in October last year. The photo is of 36-year-old Inas Abu Maamar, sobbing while holding the sheet-clad body of her 5-year-old niece, Saly, in the morgue of Nasser hospital in Khan Younis. A photo taken 10 days in, wins an award while the genocidal violence continues. It is “profoundly affecting” according to a jury member. Two hundred days on, and the image has been repeated hundreds of times across the Gaza Strip.

A decade ago, in 2013, Paul Hansen won the World Press Photo award for another photo of dead Palestinian children. The shroud-wrapped bodies of two-year-old Suhaib Hijazi and his elder brother Muhammad, almost four, are carried by their uncles through the streets of Gaza to their funeral. Echoes and palimpsests. Each a new tragedy, repeating over and over again. How do we imagine differently?

Two hundred days and 75 years. Here in Australia tomorrow is also ANZAC day, where there are national commemorations paying respects to those who served in WWI, but increasingly about veterans through all the warring the colony of Australia has engaged in.

On ANZAC Day the frequent refrain is ‘Lest We Forget’. We can resist the jingo-ism of nationalistic narrative-writing that tells us Australia ‘came of age’ in WWI; we can acknowledge that wars are fought by violent, patriarchal, colonial, capitalist power-hungry states devouring the bodies, minds, and lives of those on the front line.

We can acknowledge that states like Australia are actively investing in the companies that build bombs and program drones, and they persist in this while crying crocodile tears over the human suffering in Gaza. We can question how politicians can stand and lay wreaths with rosemary pinned to their chest, head bowed as the last post plays—Lest We Forget—before they go into their office the next day and sign off on contracts and diplomatic decision-making in profound complicity in ongoing genocide.

Lest We Forget that honouring those who have died means we can choose peace now.

Two hundred days. Fourteen thousand dead children. Hundreds of thousands of children living in tents, slowly starving. What does hope look like right now? Solidarity encampments. Freedom flotillas. But also, Palestinian children telling their own stories. Fourteen-year-old Lujayn tells of the arrival of Israeli bulldozers to flatten their house while they were still in it. Nine-year-old Lama Abu Jamous, reporting from Gaza.

I wish I had never heard of Hind Rajab.

What if we ask what does a world look like where we don’t need dead children to animate our rage? What if we ask how we can change the structures that keep churning out tiny dead and damaged bodies instead? I want to imagine this in community. In solidarity. In hope. Together.

Leave a comment